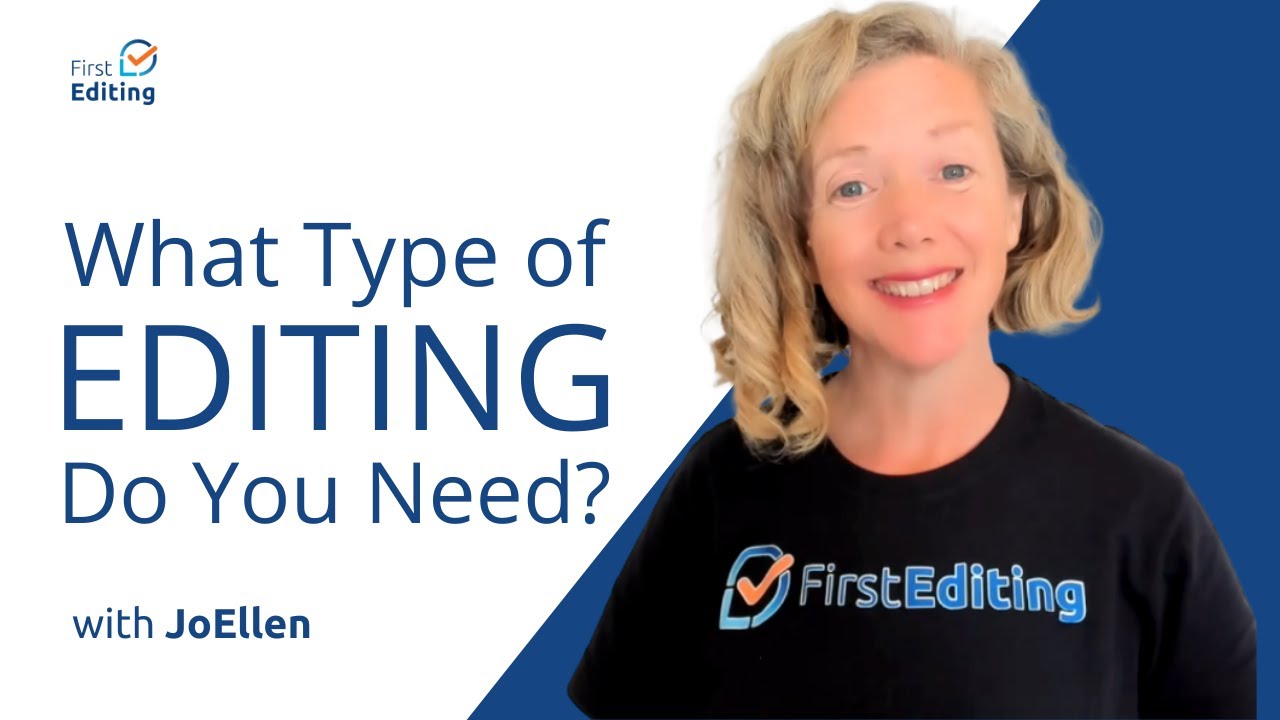

In this episode, Hayley Milliman, the content lead for ProWritingAid, joins JoEllen Nordstrom to talk about the often-used admonition from an editor to a writer to show, don’t tell.

We at FirstEditing love and partner with ProWritingAid so much because they have a fantastic online platform that helps you become a better writer, and they teach you so much. It’s not just improving your work; you really get to learn. It’s a fantastic program; a grammar guru style editor and a copy editor all in one package. It’s like a writing mentor there. They have reports and different tools that we use every day with all our professional editors too.

Learn what show, don’t tell means, and how it will help you become a better self-editor so you can improve your writing skills now.

What Show, Don’t Tell, Means

Basically, show, don’t tell means that you are letting your reader do a little bit too much work, more mental heavy lifting. A great example of telling is saying, “Hayley is sad.” I’m telling you I am sad. It’s very boring. It’s kind of quick and to the point. It doesn’t really create an engaging character experience. That is telling.

Our goal is always to show, further engaging the reader, so instead of saying “Hayley is sad,” I’ll use language to show them I’m sad. So I might say, “Hailey’s lower lip trembled and a tear rolled down her cheek.”

As the reader, you are able to make an assumption correctly that Hayley is sad, but it’s not just forced down your throat; it’s not just told. And it’s really creating a more vivid experience. If you’re not able to visualize the scene clearly, when you kind of focus just on Hayley is sad, Hayley was hungry, Hayley goes to the store again, it’s like too simple an experience without any engagement.

I get it; that makes sense. I think it comes back to, who are you talking to? Who is your audience? Who are you writing for? I know that before, you mentioned a couple of ideas, like your words are creating a movie in our minds for each of the readers to see.

Who is the one who’s going to watch your movie and why, and what did they want to get out of it? The story basically has an event and a conflict and a resolution, but the journey is why we decided to join you. I think that’s really good.

How Does Show, Don’t Tell Affect the Reader’s Experience?

Typically, when you’re telling rather than showing, you’re using less evocative language. So if I’m saying, “Hayley is sad,” I’m creating a less evocative and less engaging experience for my reader. My goal will always be to try to create an engaging experience where the reader really feels immersed.

Obviously that changes depending on whom you are writing for. So if I’m writing for five-year-olds, like kindergarteners, “Hayley is sad” might be perfectly fine because that is likely all they can handle. But when you are writing for adults, you really want to use language in a way that drops them into the scene a

nd lets them do some heavy lifting and interpreting on their own.

Sometimes the writing comes with a description, and comes in with dialogue as well. We see this a lot with ProWritingAid; people tend to use dialogue tags, kind of like tell how a character is. Same as Hayley shouted or Hayley hurt, like using those exceptional dialogue tags that convey meaning rather than having the meaning be in what the person is saying.

When you’re thinking about a show, you want to think, how can I use the language of the dialogue, of my description, to show what I mean rather than telling the reader what I mean. So, instead of saying, “Hayley fumed at her mother,” say something like, “Put your tissues away,” Hayley’s mother fumed.

Make the dialogue itself show that my mom is mad at me. Always try to think, how can I construct these sentences in a way that I don’t have to tell the reader what I mean, but the reader can kind of infer what I mean. Infer what I mean by that way I’m using language.

We’ve talked in previous sessions about clarity. So the goal here isn’t to be too obvious getting the meaning across, nor to make it really a puzzle piece, but rather to engage the reader. You’re not trying to hide the main context of the scene, nor use complicated language, but you are trying to use evocative language. So you are always treading that line between how can I be as descriptive as possible without being overly complicated?

So again, the goal in showing is not just to be super complicated and make your reader puzzled throughout, but rather to make your reader feel right. We don’t want to read like we’re always reading an outline. We as writers ask, how can my reader be engaged? How can I make my reader feel something? How can I also not make my reader have to have a dictionary by their side trying to understand my words, yet still be engaging?

How are we achieving this show, don’t tell? We are using more tools. We are using more synonyms, the thesaurus.

How do we do That?

If we go back and we look at the writing—the subject, verb, object—it’s not so complicated here to move them around to better show rather than tell.

There are a couple of ways. The first way is looking for to be verbs, which is a good flag that you’ve used. Motion tells, such as, Hayley is this…that’s a good way to see that you’re telling rather than showing.

Obviously, some telling rather than showing is fine. It doesn’t mean that every single time someone’s sad you have to write a soliloquy about how they feel but again, you want to ask yourself, am I using this too much? Could I describe this in a way that is more engaging? To be verbs are a good way to tell.

Another way is using what I call the camera test. This is asking yourself, if I look at this, if I have a movie camera, or I took a camera or I took a photo of this scene as I describe it, would it capture all the details that I need to create that vivid picture?

If you go back to the “Hayley is sad” example, if I just said on the page, “Hayley is sad, seated at her desk,” the camera couldn’t pick up on what sad is. Like the camera can pick up on more examples when you flesh out sad. Sad is not like something the camera can see; but the camera could see tears. A camera could see a trembling lower lip. A camera could see downcast eyes. A camera could see a pale complexion. So typically, those to be verbs need more description for the camera to pick it up.

So think about that. If I were to have a movie, use a camera, would it pick up all the details that I as the author am thinking in my head? If it doesn’t, then I need to add some more in, especially when they matter. It might not matter that my lower lip trembled in a particular scene, but you want to think about where it does it matter that the camera picks up small details. Working those kinds of small details in adds more engagement to the reading experience.

Setting

The same goes for setting. If you’re just describing Arandale as beautiful, what is beautiful means a million things. Telling your reader that a specific place is beautiful doesn’t do anything, you have to give more description about what made it beautiful. I might think something in the mountains beautiful, you might think something by the sea is beautiful. So you have to add those details, and again, think about that camera. Could the camera pick up the way the pebble stone stripes glisten in the sand? Could the camera pick up the way castle turrets reach towards the sky? Or something like that. And that’s what you’re thinking, in my scene, is the camera picking up all these small details that I as the writer have thought about? If not, and then if you’re saying, oh no, actually, this isn’t on the page. I need to add that back in. So the camera test is really big, and that’s something you do when you’re re-reading a scene, when you’re re-reading your book, thinking again, could this camera pick up all the small details?

How can ProWritingAid help?

If my book is adapted by a director, will it be true to my vision? Or will it go wildly off because I haven’t given enough details? ProWritingAid can help. We have in our style report, and then our sensory report, ways to pick up this emotion tells so it can pick up places where you’re using those to be verbs and just saying, felt sad, felt scared, felt whatever, and it can flag those for you and let you know oops, I’ve done that, maybe I should change it.

And we also have a sensory report which tells you which language using to like, do you kind of the five senses, so taste, smell, etcetera, because typically, if you’re not using sensory words too often, then you’re likely telling and not showing. When you really add on those small details about how things taste and what they look like and what the sounds are like, it’s going to become more showing than telling.

One of the things that I like to mention here is the reports on ProWritingAid. They plug in with two of my favorite tools, which are Fictionary’s StoryTeller and Story Coach, and that really we covered. (If you want our podcast, here we have the other 38 Story Elements, and it does go into the scene, the location, the character, and senses.)

One of the great things to have is a checklist. When you have a checklist, you don’t omit anything so by using these tools, ProWritingAid and Fictionary, which we use as your editors, then you’re learning not only how to not miss anything, but you’re learning to naturally think about these things all the time. Prolific writers, especially independent fiction writers, tend to write with the next series already planned out, and I think it’s really great. I love how these two tools, ProWritingAid and Fictionary, actually work together; we don’t have to plug them together, they are automatically already playing together very well to look at the scene and to make sure you see things, but sometimes you want to taste it, sometimes you want to feel it. There are different things ProWritingAid and Fictionary use to prompt you so you are using all the senses from all the different angles.

Using Weather

Are you using the weather in your scenes? How does that affect you? Does the weather do anything to help you? Does it set a mood? Say your character is sad, but the tear was hidden in the rainwater running down her face, so then it’s less likely the other character will see it. There are a lot of writing tools out there but it’s not easy to know which ones to use, and ProWritingAid and Fictionary together are really, really good. The reports are so helpful.

A lot of times, as writers we have this scene in our head, like when we’re planning something, we’re visualizing it, and we know it. But the act of writing is so hard, that activity is exhausting, it’s super hard, so when you’re doing it, you probably did have a very clear idea of what was happening, what the weather was like, what was going on, but it doesn’t always make it onto the page. And that’s again where these tools, ProWritingAid and Fictionary, can come in and help you.

It’s like a kind of little nudge that say, “Hey, Hayley, you have this great idea but it didn’t quite make it here because you’re probably really tired when you’re writing the scene.” So, you’ve done a lot of telling rather than showing. Then you get that little nudge that says, “Hey, remember that scene? The scene you meticulously spent hours thinking about? You’re not doing a great job conveying the meaning and conveying what’s going on. You really need to take a look at this again and try to add some of those sentences back in.” Yes, writing is tiring, and it’s really hard for a lot of us to try to get all this, to get what’s locked in our heads, onto the page.

It takes time. And ProWritingAid is like having an intelligent assistant and writing mentor right there, kind of just nudging you the entire time because it’s really hard and I want to mention that in today’s world, if your objective is to become a bestselling author or to have a mass audience of readers, there are millions, literally millions, of people at their computers, also with the same objective. So you need to have a very definite purpose. You need to plan. You need to use all the tools available that can help you improve and make your writing better because it’s more than the actual sitting down and doing your time. It’s actually achieving your goals that makes a difference. I really do like that. So when thinking about show, don’t tell, we need to go back and look at all these sentences, again at the sentence level, and at those to be verbs. But you do also want to look on the larger level for show, don’t tell, per scene.

You can make those show, don’t tell, changes at the sentence level but you want to be reading at scenes one by one because like I said, some to be verbs are fine, but you want to think about the camera test: is this capturing the entire scene in a way that I would want it to? And for that you do need to zoom out a little bit. So you’ve started with your sentences to make sure you’re not using too many to be verbs but you do want to look at the larger level and see the whole thing flow. Ask yourself, am I capturing it in a way that will translate well to a film? I’m not saying that your book has to go that way, but your reader wants to play, like we talked about a couple of sessions ago.

That movie that your reader’s playing in their head, is it clear? Is it capturing? Is there a chance your reader might think you’re sitting by the beach instead of in the mountain air? If you want to make sure that it’s very clear, very engaging, and very evocative for them, anchor your scene from the beginning; make sure it’s contacting all the senses.